I have a strange gratitude for the assholes in my life. Not because they’re right. Not because they’re kind. But because they trained me in ways comfort never could.

That wasn’t always true for me.

For a long time, I did what most people do. I tried to change them. I argued, explained, negotiated, withdrew, drew lines in the sand, redrew them, and told myself I was being “healthy.” When that didn’t work, I left—sometimes physically, sometimes emotionally—convinced I was protecting my peace.

What I was really doing was avoiding the work.

I mistook distance for wisdom. I mistook cutting people off for strength. Sometimes that distance was necessary. Often it was just easier than staying present with my own reactivity.

It took me a long time to see what I was throwing away.

The people I labeled difficult were showing me—without fail—where I still tightened, where I still wanted control, where I still lost my center and blamed them for it. Instead of learning, I tried to manage the environment. Instead of growing, I tried to curate my life into something smoother.

That never worked for long.

Eventually, I stopped resenting the people who challenged me and started paying attention to them. Not to fix them. Not to tolerate everything. But to observe myself in their presence. To notice what rose up. To take responsibility for my own reactions.

That’s when their value became clear.

I’m not the first person to notice this. I stand on the shoulders of giants who figured it out long before me.

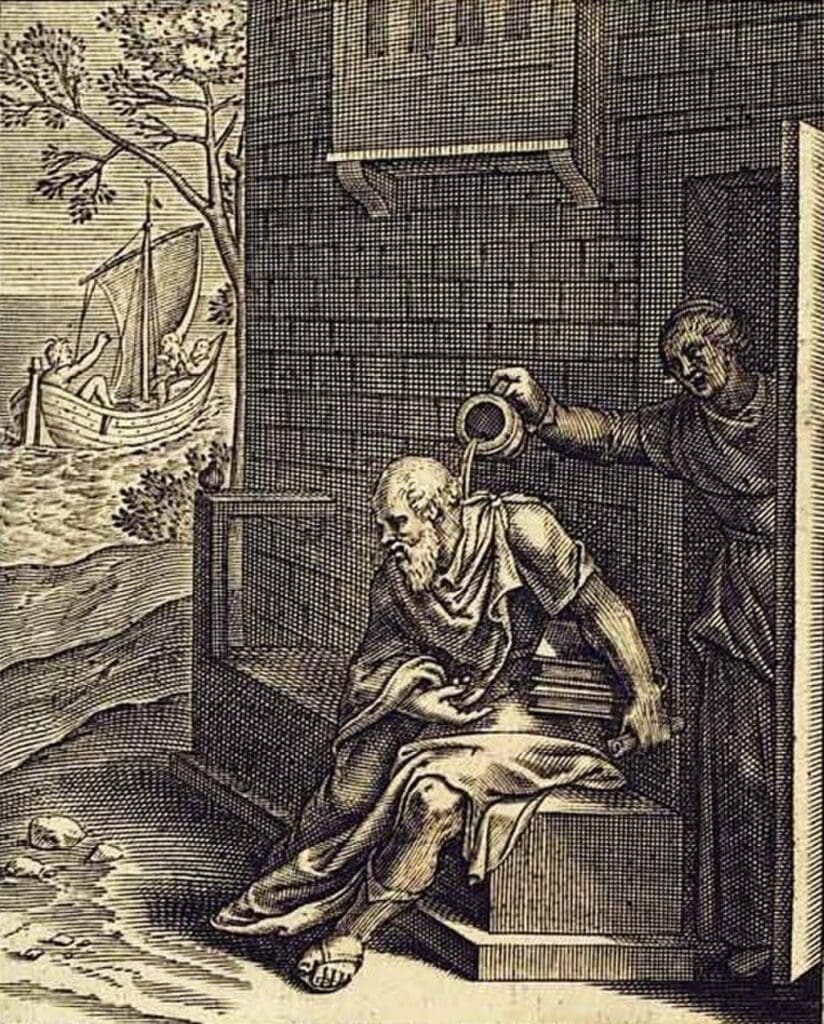

Socrates lived with a woman whose name became synonymous with being unbearable. Xanthippe is remembered as sharp-tongued, volatile, and publicly humiliating. She nagged, scolded, and—on at least one recorded occasion—dumped the contents of a chamber pot on Socrates’ head.

By any contemporary framework, he could have framed himself as unlucky, mistreated, or trapped in a toxic marriage. He didn’t.

He claimed the opposite: that without his wife, he would never have become as virtuous, as patient, or as unshakeable as he was.

Socrates understood something most of us resist: difficulty is not always a problem to be solved. Sometimes it is a gift.

Just as a wrestler becomes skilled only through regular engagement with a strong opponent, Socrates saw his wife as a constant, unavoidable instructor. She trained him in restraint. In patience. In remaining calm and centered in the presence of emotional volatility.

What appeared to others as domestic misery, he treated as daily practice in self-mastery. Later, when he went into the streets of Athens to philosophize, the insults of strangers barely registered. Compared to what he had already learned to endure at home, the world was easy.

As recorded by Xenophon in Memorabilia:

“It is the example of the rider who wishes to become an expert horseman: ‘None of your soft-mouthed, docile animals for me,’ he says. ‘The horse for me must show some spirit’; in the belief, no doubt, that if he can manage such an animal, it will be easy enough to deal with every other horse besides. And that is just my case. I wish to deal with human beings, to associate with man in general; hence my choice of wife. I know full well, if I can tolerate her spirit, I can with ease attach myself to every human being else.”

And this is the part people miss when they read that passage.

It’s not about tolerating difficulty.

It’s about who you become beneath it.

I like myself more because of the assholes in my life. I like the version of me that grew a spine, developed restraint, learned precision instead of reaction. I like the steadiness that wasn’t gifted to me by ease, but forged by friction.

There’s a quiet confidence that comes from having been tested.

Interactions with difficult humans that send other people into spirals barely register for me. Slights. Moodiness. Passive aggression. Chaos disguised as urgency. I’ve already done my reps elsewhere. My nervous system recognizes the pattern and doesn’t rise to meet it.

Work, in particular, is almost laughable by comparison. Coworker tension? Office politics? Emotional immaturity with a badge and a title? pffft. I have better sparring partners at home. I practice staying centered when the stakes are real—when the emotions are personal, when escape isn’t the default option.

Don’t confuse calm with weakness.

And don’t mistake tolerance for submission.

What looks like ease now is actually capacity. What looks like detachment is earned scale. When you’ve learned to hold yourself steady in the presence of someone who can truly get under your skin, the rest of the world loses its teeth.

That’s the gift.

Not that difficult people become nicer.

But that fewer people—and fewer moments—have the power to move you.

That’s why I don’t resent the difficult people in my life. I don’t romanticize them. I don’t excuse harm. But I do recognize training when I see it.

They don’t break me.

They build me.

And I like who I am because of that gift.